Removing the nonessential is a key element of simplicity, yet deceptively difficult to accomplish. We need reminding. I was reminded today while looking out the window at home at our pine tree which is in great need of pruning. Our own lives need a conscious self-pruning of sorts to stay focused on what is important. (Click Keynote slide above for actual size.)

Author Archives: Ichi-go-ichi-e

Students begin presentation today by referencing cognitive scientist Ken Mogi

My students Yuuki and Ryuki begin their presentation by challenging students to “use their brains.” Delighted and surprised to see them use the image of the famous Japanese scientist, Mogi-san. The class got a kick out of that – I think the students really like Ken and his popular books, etc. If you are interested in some of Dr. Mogi’s work, check out his Qualia site: http://www.qualia-manifesto.com/

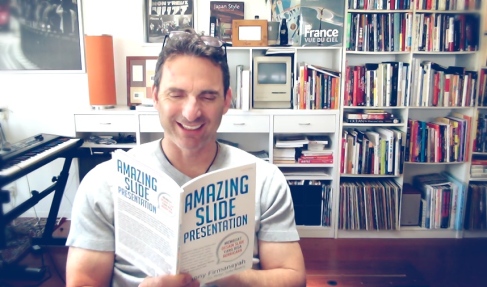

Taking a look at Dhony Firmansyah`s new presentation book. Really nice!

In my office in Nara, Japan with a great book sent to me by Dhony Firmansyah in Indonesia. Now I just have to study Indonesian and I will be set. Very nicely designed book. Loads of examples.

Nothing is more important than mom

Today is Mother’s Day. Almost three years ago—and the last time I visited the USA— my mother passed away by my side at the age of 82. After three years I do not miss her any less—I miss her much more. Below, I’d like to tell you a little bit about my last moments with my mother, a story I shared with a few people before.

Above are a couple of snapshots of my mother taken when she was in her 20s. Mom and dad were both 19 on their wedding day (still from 8mm film). Her eyes and smile were engaging and remarkable then, and they remained so throughout her entire life. If you ask people who knew her — or met her even once — they will always describe her in terms of her sweet smile or happy, engaging eyes. They say the eyes are the window to the soul; in her case it is certainly true.

After suffering a major stroke in 1996, my mother’s final years on this planet were spent here in the Nahalem Valley (lower left in distance of photo). For years my oldest brother took my mom for long rides every week in this beautiful setting; she loved it. This spot on Neahkahnie Mountain was one of her favorite places to park and have a cup of coffee. I would visit Oregon every chance I could from Japan and also spend hours driving with her around this inspirational part of the world. Especially when the weather is good, it’s impossible to grow tired of the natural beauty here. I’m too young to remember, but when my brother’s were small, my family had a summer cabin on the beach pictured here (the second photo is a still from 8mm film of a trip mom and dad took with my oldest brother to Neahkahnie Beach in 1952, nine years before I was born.)

“Death ends a life but not a relationship”

Three years ago we rushed to Oregon from Japan to be with my mother on her final days. The day we arrived we introduced our daughter to her American grandma (above). As you can see in the photo, my mom’s eyes lit up like a christmas tree when she saw her new granddaughter. This was the last time she ever smiled.

The next few days we’d all take turns being by my mother’s side. On June 4, 2010, on the drive down from Seaside to see my mother, I stopped by Neahkahnie Mountain alone briefly to reflect one time more and to say a little prayer. The warmth of the sun juxtaposed with the cool breeze flowing off the blue Pacific Ocean far below was invigorating, even as all my thoughts were on my mother and all the times we had spent together in this exact spot many times before. After twenty minutes, I drove down to the Nehalem Valley Care Center a few miles away.

As I entered her room I was relieved to see her still breathing. Her breaths were shallow but thankfully less labored than the night before. She had been unconscious for days now. She looked peaceful. The staff had been very skilled and also remarkably caring throughout this entire process. They were very concerned for her and made sure that she was in no pain or suffering in any way yet very mindful that the family needed time with her. I kissed her forehead and told her that I was here, that I was not going anywhere, and that I loved her. I pulled up a chair next to her bed and opened up my book Tuesday’s with Morrie. For the next hour I read a page or two and then stopped to hold her hand or talk to her. The room was bright and cheery in a kind of bitter-sweet way due to the beautiful weather outside. Sunbeams were even kissing the edge of her white pillows. There was a certain calmness and peacefulness in the air that I can not explain.

After about an hour of sitting next to her in this way, I continued reading a few sentences in the book when I glanced over at her chest expecting, of course, to see that she was still breathing. I took notice immediately that her chest had suddenly stopped moving. But her breathing was very slow now so perhaps, I thought, if I just wait a few seconds I will see her inhale and her chest expand once again. Two seconds, then five seconds, then ten…nothing. I change my position and bring my face closer to hers. Nothing. Her mouth is slightly open, but still. Then one last very, very tiny breath from her mouth, halfway between a breath and a gentle gulp…and then complete silence, except for the bird chirping outside and the low hum of the oxygen tank next to the bed. That was it. I just saw my mother’s final, gentle breath of life. I entered the hall and quietly asked for the charge nurse. He entered the room with a somber yet empathetic look on his face. Without saying a word, he softly placed his stethoscope on her chest. After a few moments: “There is no heart beat,” he whispered to me. “I’m sorry.” The nurse then bent down to turn off the oxygen tank which caused the room to become completely silent save for the occasional bird singing in the garden next to the window. I did not hear what the nurse said after that, but I asked to be alone in the room for a few minutes with my mom. “Take as much time as you need,” he said, and then he quietly closed the door.

After about an hour of sitting next to her in this way, I continued reading a few sentences in the book when I glanced over at her chest expecting, of course, to see that she was still breathing. I took notice immediately that her chest had suddenly stopped moving. But her breathing was very slow now so perhaps, I thought, if I just wait a few seconds I will see her inhale and her chest expand once again. Two seconds, then five seconds, then ten…nothing. I change my position and bring my face closer to hers. Nothing. Her mouth is slightly open, but still. Then one last very, very tiny breath from her mouth, halfway between a breath and a gentle gulp…and then complete silence, except for the bird chirping outside and the low hum of the oxygen tank next to the bed. That was it. I just saw my mother’s final, gentle breath of life. I entered the hall and quietly asked for the charge nurse. He entered the room with a somber yet empathetic look on his face. Without saying a word, he softly placed his stethoscope on her chest. After a few moments: “There is no heart beat,” he whispered to me. “I’m sorry.” The nurse then bent down to turn off the oxygen tank which caused the room to become completely silent save for the occasional bird singing in the garden next to the window. I did not hear what the nurse said after that, but I asked to be alone in the room for a few minutes with my mom. “Take as much time as you need,” he said, and then he quietly closed the door.

I grabbed a towel and covered my face as I wept next to my mother, using the towel to soak up the tears so that the staff would not see. After a few minutes I pulled myself together. I was feeling great sadness, of course, but also a strange sense of peacefulness and calm came over me. Perhaps this is what they call closure. In any event, I was happy that I can be sure now that she is not suffering or sad in any way. I am also feeling so blessed that I could be there to witness my mom’s very last breath of life. I will always remember and cherish the experience of being by her side at the end. I was able to witness the last breath of the woman who gave me my first. This is the circle of life. Yes, it is a very sad, sad feeling, but it is also a beautiful one at some level which I am not clever enough to put into words. I do not feel that she is gone in a sense. Her body, which is after all a kind of ephemeral vessel, is dead, but the relationship does indeed live on. My mom will always be a big part of my life.

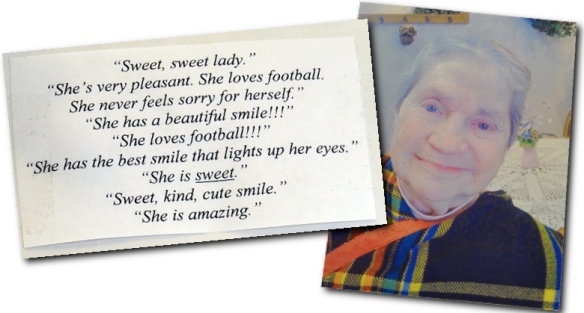

ABOVE: When I arrived at the care center, about 10 days before my mother passed, I noticed a picture of my mother on the wall: “Resident of the Month” it said on the frame. Below that was a sample of some of the thoughts that people had written about her. Even though she could not speak, it was her happy smile and gentle eyes that made such an impression with people. She had a way of making people feel better about themselves. Mom is an inspiration for me and always will be. If I can be 1/10th as “amazing” as everyone thought mom was, I’ll consider myself very lucky indeed.

Happy Mother’s Day, everyone. There is nothing more important than (a) mom.

Had a great time at the British Embassy in Tokyo today. Great crowd!

Daughter listens to live rock-n-roll at outdoor concert in Osaka

Image

My daughter and I sat down outside at ATC (Osaka Bay) to listen to some pretty good young bands play. The event was organized to raise money for the Tohoku tsunami recovery efforts.

10 Simple Life Lessons from the Bamboo

The forests that surround our village here in Nara, Japan are filled with beautiful bamboo. The practical, aesthetic, and spiritual significance of bamboo is deeply embedded in Japanese culture. The particular part of Nara where we live is famous for myriad bamboo products, such as tea whisks, tea utensils, knitting needles, and so on. The symbolism of the bamboo plant runs deep and offers practical lessons for life and for work. Below I list ten ways in which the bamboo offers up for us practical lessons. Nature is always speaking to us and providing lessons. We only need to improve our ability to hear with our eyes and see with our ears to appreciate her lessons.

The forests that surround our village here in Nara, Japan are filled with beautiful bamboo. The practical, aesthetic, and spiritual significance of bamboo is deeply embedded in Japanese culture. The particular part of Nara where we live is famous for myriad bamboo products, such as tea whisks, tea utensils, knitting needles, and so on. The symbolism of the bamboo plant runs deep and offers practical lessons for life and for work. Below I list ten ways in which the bamboo offers up for us practical lessons. Nature is always speaking to us and providing lessons. We only need to improve our ability to hear with our eyes and see with our ears to appreciate her lessons.

(1) Remember: What looks weak is strong

The body of even the largest type of bamboo is not large compared to the other much larger trees in the forest. But the plants endure cold winters and extremely hot summers and are sometimes the only “trees” left standing in the aftermath of a storm. Remember the words of a great Jedi Master: “Size matters not. Look at me. Judge me by my size do you?” We must be careful not to underestimate others or ourselves based only on old notions of what is weak and what is strong. You do not have to be big and imposing to be strong. You may not be from the biggest company or the product of the most famous school, but like the bamboo, stand tall, believe in your own strengths, and know that you are as strong as you need to be. Remember too that there is strength in the light, in openness and transparency. There is strength in kindness, compassion, and cooperation.

The body of even the largest type of bamboo is not large compared to the other much larger trees in the forest. But the plants endure cold winters and extremely hot summers and are sometimes the only “trees” left standing in the aftermath of a storm. Remember the words of a great Jedi Master: “Size matters not. Look at me. Judge me by my size do you?” We must be careful not to underestimate others or ourselves based only on old notions of what is weak and what is strong. You do not have to be big and imposing to be strong. You may not be from the biggest company or the product of the most famous school, but like the bamboo, stand tall, believe in your own strengths, and know that you are as strong as you need to be. Remember too that there is strength in the light, in openness and transparency. There is strength in kindness, compassion, and cooperation.

(2) Bend but don’t break.

One of the most impressive things about the bamboo is how it sways with the breeze. This gentle swaying movement is a symbol of humility. The foundation of the bamboo is solid, yet it moves and sways harmoniously with the wind, never fighting against it. In time, even the strongest wind tires itself out, but the bamboo remains standing tall and still. A bend-but-don’t-break or go-with-the-natural-flow attitude is one of the secrets for success whether we’re talking about bamboo trees, answering tough questions in a Q&A session, or just dealing with the everyday vagaries of life.

(3) Be strongly rooted yet flexible

The bamboo is remarkable for its incredible flexibility. This flexibility is made possible in part due to the bamboo’s complex root structure which is said to make the ground around a bamboo forest very stable. Roots are important, yet in an increasingly mobile world many individuals and families do not take the time or effort to establish roots in their own communities. The challenge, then, for many of us is to remain the mobile, flexible, international travelers and busy professionals that we are while at the same time making the effort and taking the time to become involved and deeply rooted in the local community right outside our door.

(4) Slow down your busy mind

We have far more information available than ever before and most of us live at a very fast pace. Even if most of our work life is on-line, life itself can seem quite hectic, and at times chaotic. Often it is difficult to see the signal through all the noise. In this kind of environment, it seems all the more important to take the time to slow down, to calm your busy mind so that you may see things more clearly.

(5) Be always ready

As the great Aikido master Kensho Furuya says in Kodo: Ancient Ways, “The warrior, like bamboo, is ever ready for action.” In presentation or other professional activities too, through training and practice we can develop in our own way a state of being ever ready. Through study and practice we can at least do our best to be ready for any situation.

(6) Find wisdom in emptiness

It is said that in order to learn, the first step is to empty ourselves of our preconceived notions. One can not fill a cup which is already full. The hollow insides of the bamboo reminds us that we are often too full of ourselves and our own conclusions; we have no space for anything else. In order to receive knowledge and wisdom from both nature and people, we have to be open to that which is new and different. When you empty your mind of your prejudices and pride and fear, you become open to the possibilities.

(7) Smile, laugh, & play

The Kanji (Chinese character) for smile or laugh is 笑う. At the top of this character are two small symbols for bamboo (竹 or take). It is said that bamboo has a strong association with laughter, perhaps because of the sound that the bamboo leaves make on a windy day. If you use your imagination I guess it does sound a bit like the forest laughing; it is a soothing sound. Bamboo itself also has a connection with playfulness as it has been used for generations in traditional Japanese kite making and in arts and crafts such as traditional doll making. We have known intuitively for generations of the importance of smiling, laughing, and playing, now modern science shows evidence that these elements play a real and important role in one’s mental and physical health as well.

Above. This is the bamboo forest behind our home in Nara. I took this short clip from the back of our house on New Year’s eve. Note the soothing sound of the bamboo as it sways in the strong wind.

(8) Commit yourself to growth & renewal

Bamboo are among the fastest-growing plants in the world. It does not matter who you are — or where you are — today, you have amazing potential for growth. We usually speak of Kaizen or continuous improvement that is more steady and incremental, where big leaps and bounds are not necessary. Yet even with a commitment to continuous learning and improvement, our growth — like the growth of the bamboo — can be quite remarkable when we look back at what or where we used to be. You may at times become discouraged and feel that you are not improving at all. Do not be discouraged by what you perceive as your lack of growth or improvement. If you have not given up, then you are growing, you just may not see it until much later. How fast or how slow is not our main concern, only that we’re moving forward.

(9) Express usefulness through simplicity

Aikido master Kensho Furuya says that “The bamboo in its simplicity expresses its usefulness. Man should do the same.” Indeed, we spend a lot of our time trying to show how smart we are, perhaps to convince others — and ourselves — that we are worthy of their attention and praise. Often we complicate the simple to impress and we fail to simplify the complex out of fear that others may know what we know. Life and work are complicated enough without our interjecting the superfluous. If we could lose our fear, perhaps we could be more creative and find simpler solutions to even complex problems that ultimately provide the greatest usefulness for our audiences, customers, patients, or students.

Aikido master Kensho Furuya says that “The bamboo in its simplicity expresses its usefulness. Man should do the same.” Indeed, we spend a lot of our time trying to show how smart we are, perhaps to convince others — and ourselves — that we are worthy of their attention and praise. Often we complicate the simple to impress and we fail to simplify the complex out of fear that others may know what we know. Life and work are complicated enough without our interjecting the superfluous. If we could lose our fear, perhaps we could be more creative and find simpler solutions to even complex problems that ultimately provide the greatest usefulness for our audiences, customers, patients, or students.

(10) Unleash your power to spring back

Bamboo is a symbol of good luck and one of the symbols of the New Year celebrations in Japan. The important image of snow-covered bamboo represents the ability to spring back after experiencing adversity. In winter the heavy snow bends the bamboo back and back until one day the snow becomes too heavy, begins to fall, and the bamboo snaps back up tall again, brushing aside all the snow. The bamboo endured the heavy burden of the snow, but in the end it had to power to spring back as if to say “I will not be defeated.”

Above. The bamboo bends in winter when the snowfall is heavy, but springs back when the snow has melted.

These are just ten lessons from the bamboo; one could easily come up with dozens more. These are not things that we do not all ready know, of course. Yet like many a good sensei, the bamboo simply reminds us of what we already know but may have forgotten. Then it is up to us to put these lessons (or reminders) of resilience into daily use through persistence and practice. You do not need to be perfect. You need only to be resilient. This is the greatest lesson from the bamboo.

Below I shared some of the lessons learned from the bamboo in this 12-minute TEDxTokyo talk which was recorded (and streamed) live from Tokyo on May 21, 2011. You can see the slides I used in this talk below on Slideshare.net. These slides were made in Photoshop and Keynote and exported as a PDF file for Slideshare.

7 Japanese aesthetic principles to change your thinking

Exposing ourselves to traditional Japanese aesthetic ideas — notions that may seem quite foreign to most of us — is a good exercise in lateral thinking, a term coined by Edward de Bono in 1967. “Lateral Thinking is for changing concepts and perception,” says de Bono. Beginning to think about design by exploring the tenets of the Zen aesthetic may not be an example of Lateral Thinking in the strict sense, but doing so is a good exercise in stretching ourselves and really beginning to think differently about visuals and design in our everyday professional lives. The principles of Zen aesthetics found in the art of the traditional Japanese garden, for example, have many lessons for us, though they are unknown to most people. The principles are interconnected and overlap; it’s not possible to simply put the ideas in separate boxes. Thankfully, Patrick Lennox Tierney (a recipient of the Order of the Rising Sun in 2007) has a few short essays elaborating on the concepts. Below are just seven design-related principles (there are more) that govern the aesthetics of the Japanese garden and other art forms in Japan. Perhaps they will stimulate your creativity or get you thinking in a new way about your own design-related challenges.

Seven principles for changing your perception

Kanso (簡素) Simplicity or elimination of clutter. Things are expressed in a plain, simple, natural manner. Reminds us to think not in terms of decoration but in terms of clarity, a kind of clarity that may be achieved through omission or exclusion of the non-essential.

Fukinsei (不均整) Asymmetry or irregularity. The idea of controlling balance in a composition via irregularity and asymmetry is a central tenet of the Zen aesthetic. The enso (“Zen circle”) in brush painting, for example, is often drawn as an incomplete circle, symbolizing the imperfection that is part of existence. In graphic design too asymmetrical balance is a dynamic, beautiful thing. Try looking for (or creating) beauty in balanced asymmetry. Nature itself is full of beauty and harmonious relationships that are asymmetrical yet balanced. This is a dynamic beauty that attracts and engages.

Shibui/Shibumi (渋味) Beautiful by being understated, or by being precisely what it was meant to be and not elaborated upon. Direct and simple way, without being flashy. Elegant simplicity, articulate brevity. The term is sometimes used today to describe something cool but beautifully minimalist, including technology and some consumer products. (Shibui literally means bitter tasting).

Shizen (自然) Naturalness. Absence of pretense or artificiality, full creative intent unforced. Ironically, the spontaneous nature of the Japanese garden that the viewer perceives is not accidental. This is a reminder that design is not an accident, even when we are trying to create a natural-feeling environment. It is not a raw nature as such but one with more purpose and intention.

Yugen (幽玄) Profundity or suggestion rather than revelation. A Japanese garden, for example, can be said to be a collection of subtleties and symbolic elements. Photographers and designers can surely think of many ways to visually imply more by not showing the whole, that is, showing more by showing less.

Datsuzoku (脱俗) Freedom from habit or formula. Escape from daily routine or the ordinary. Unworldly. Transcending the conventional. This principles describes the feeling of surprise and a bit of amazement when one realizes they can have freedom from the conventional. Professor Tierney says that the Japanese garden itself, “…made with the raw materials of nature and its success in revealing the essence of natural things to us is an ultimate surprise. Many surprises await at almost every turn in a Japanese Garden.”

Seijaku (静寂)Tranquility or an energized calm (quite), stillness, solitude. This is related to the feeling you may have when in a Japanese garden. The opposite feeling to one expressed by seijaku would be noise and disturbance. How might we bring a feeling of “active calm” and stillness to ephemeral designs outside the Zen arts?

LINKS

• Read more about The Nature of Japanese Garden Art by Patrick Lennox Tierney at Bonsai Beautiful dot com.

• Japanese Aesthetics (Stanford Encyclopedia).

• Enso: Zen Circles of Enlightenment (book)

from presentation zen

Kamishibai: Lessons in visual storytelling from Japan

Kamishibai is a form of visual and participatory storytelling that combines the use of hand drawn visuals with the engaging narration of a live presenter. Kami (紙) means paper and shibai (芝居 ) means play/drama. The origins of kamishibai are not clear, but its roots can be taced back to various picture storytelling traditions in Japan such as etoki and emaki scrolls and other forms of visual storytelling which date back centuries. However, the form of Kamishibai that one thinks of today developed around 1929 and was quite popular in the 30s, and 40s, all but dying out with the introduction of television later in the 1950s. Typical kamishibai consists of a presenter who stands to the right of a small wooden box or stage that holds the 12-20 cards featuring the visuals that accompany each story. This miniature stage is attached to the storyteller’s bicycle. The presenter changes the card, varying the speed of the transition to match the flow of the story he is telling. The best Kamishibai presenters do not read the story, but instead keep eyes on the audience and occasionally on the current card in the frame. It’s difficult to appreciate kamishibai unless you see it in action. The clip belowis of kamishibai performer Master Yassan. Even if you do not speak Japanese, this will help you get a sense for how the presenter uses visuals and narration to connect with the audience.

This clip on Youtube gives you a feel for kamishibai from 1959, a time when most gaito kamishibaiya (kamishibai storytellers) were decreasing in number as TV was becoming popular in the home.

Visual, simple, & clear

Although Kamishibai is a form of visual storytelling that originated more than eighty years ago, with roots that go back centuries in Japan, the lessons from this craft can be applied to modern multimedia presentations. Tara McGowan, who wrote The Kamishibai Classroom, says that Kamishibai visuals are more like the frames from a movie. “Kamishibai pictures are designed to be seen only for a few [moments], so extraneous details detract from the story and open up the possibilities of misinterpretation.” It’s important to design each card, she says, “…to focus the audiences attention on characters and scenery that are most important at any given moment.” If your material includes a great deal of detail that can not be eliminated, then Kamishibai may not be a suitable method to tell your story, McGowan says. But if “clarity and economy of expression are the goals, it would be hard to find a more perfect medium.” It’s easy to imagine how we can apply the same spirit of kamishibai to our modern-day presentations that include the use of multimedia and a screen.

Above: Note how the visual fills the entire card yet maintains a level of empty space. Even when text and graphics appear on the the same card, they are for the most part free of clutter. Elements often bleed off the edge which allows the element to appear larger. (Photo by Aki Saito.)

Lessons for today’s presentations from kamishibai

There are many lessons that we can apply to modern presentations given with the aid of multimedia. Here are just five things to keep in mind.

(1) Visuals should be big and bold.

Visuals in Kamishibai are big and bold and easy to see for an audience. Remember: “Design for the last row” is our mantra. This “big and bold” approach is different from picture books which have more detail since they are seen by an individual reader. In the same way, minute visual detail on screen is not appropriate for most presentation contexts as those details are too difficult to see. If you have loads of detail — and if it is crucial that people see it— a handout may be more appropriate.

(2) Visuals may bleed off the edge.

The Kamishibai visuals must not be cluttered. The entire card is used and yet much of the card may be empty which allows the positive elements on the canvas to pop out more. Elements also may bleed off the edge or appear hidden. Our brains will fill in the missing bits which fall off the edge. This makes the images appear larger and simpler than if all elements were crammed in to fit all inside the frame.

(3) Visuals may take an active role.

The visuals are not just an aid, they are a necessary part of the show. The storyteller decides when the focus will be on him and his narrative and when the focus is on the visual. It’s a balance among the visual and the aural from the point of view of the audience, and a balance of telling and showing in a smooth harmonious flow of events from the point of view of the presenter.

(4) Aim to carefully trim back the details.

Kamishibai is different from picture books in the same way that a document is different from a live, visual presentation. The presentation by its very nature omits many visual details and includes only those details which are necessary to tell the story clearly. A kamishibai performance like, say, a TED-style presentation, uses visuals to amplify meaning through simplification.

(5) Make your presentation participatory.

Even though we are using visuals, human-to-human connections are still key. Kamishibai performers of old really got the kids involved in the performance. Kamishibai is not like TV, where you just sit there. A good kamishibai performer elicited responses and totally engaged his audience. Interestingly, some kamishibai masters from the 1950s noted that their young audiences became less engaged and were more passive as TV became popular. Kids became used to just sitting in front of content rather than engaging with it. Today, however, as much as possible, we must aim to make our presentations as participatory as the context allows. This is the real lesson from the kamishibai masters.

LINKS

• iPad gives ‘kamishibai’ stories a new lease on life (app).

• Kamishibai in the classroom (in America) video.

from presentation zen

7 Important Communication Lessons from the Japanese Bath

Looking back twenty years, I had only been living in Japan a couple of months when I found myself sitting in a large Japanese bath surrounded by my naked coworkers. I was at an onsen (温泉), or Japanese hot springs, along with everyone else from my office, as part of our company weekend retreat. The purpose of the trip was not work, but simply relaxation, dining, drinking, and a little fun with colleagues. By getting away from the formality of the office setting, my boss told me, staff and managers can experience more natural communication and build better relationships which will be good for business in the long term. Eating and drinking are part of the onsen experience, and so is communal nude bathing which is thought to strengthen bonds among team members. This is when I first learned of the phrase Hadaka no Tsukiai (裸の付き合い) which means naked relationship or naked communication. My boss informed me that the Japanese bath is an important part of the Japanese way of life, and the ritual itself is also a kind of metaphor for healthy communication and good relationships. Through mutual nakedness we are all the same, he said. When you remove the formalities and the barriers through communal relaxation in the bath, you create a sort of skinship which leads to more honest, clearer communication. At least in theory, then, the hierarchical nature of Japanese relationships begin to ease as one soaks with others.

Connection with nature

The ofuro (お風呂), or Japanese bath, is an integral part of Japanese life. Just as the meaning of Japanese cuisine goes far beyond sustenance, the significance of the bath goes far beyond merely washing. For generations the sentō (銭湯) or “bath house” was a focal point in residential areas and a gathering place not just for bathing but for chatting, meeting friends, and generally feeling connected to others in the neighborhood. Today there are fewer sentō as all modern homes have a private bath, but the significance of the bathing ritual — whether at home, visiting an onsen, or at the local sentō — runs deep in the Japanese approach to life, which traditionally is closely tied to nature.

It may not seem like it sometimes in the ultra modern, fast-paced urban centers like Tokyo or Osaka, but nature, or shizen (自然), also plays a central role in Japanese culture. For many, the bath is a time for relaxation and contemplation and connecting with the natural surroundings outside the ofuro. The famous Zen scholar Daisetz Suzuki (1870-1966) often discussed the deep affection Japanese have for nature and how the yearning for that connection was something deep in all of us. “However ‘civilized,’ however much brought up in an artificially contrived environment,” Suzuki-sensei said, “we all seem to have an innate longing for primitive simplicity, close to the natural state of living.” The bathing ritual is a chance, then, to take some time off the grid of daily life and reconnect to that simple, natural state of living.

ABOVE: An older style of sentō. Although the public bath in the cities usually lacked the beautiful natural surroundings of an onsen, attempts were made to help visitors at least feel a bit of nature through large wall paintings. Fuji-san is a popular subject. (Photo source.)

ABOVE: The water in an onsen is extremely hot. Notice the washing area in the background. You sit on the wooden stools and use a bucket or shower with soap and a washcloth to thoroughly wash before entering the the large bath. The changing area is separate from the shower and bathing area.

ABOVE: The outdoor bath — rotenburo — is a particularly popular style of onsen bath. Here one feels the closest connection with nature.

Above: These are examples of private baths that came with our room at two onsens we visited in recently. The washing areas are just outside the photos. These type of onsen resorts also have large communal baths inside and outside for guests to use.

Above: It is not uncommon for brand new houses in Japan to have such a beautiful ofuro. Although most home bathrooms are not yet so beautifully designed, the basics of a shower/washing area and a deep bath which are both separate from the changing area is typical. It’s not uncommon for new houses and remodeled homes, however, to included such aesthetically pleasing bathrooms. The showrooms at interior design centers such as Panasonic are packed on weekends. Checkout samples here. (Bathrooms, remember, are just that: bath rooms. The toilet has its own room unattached to the bathing area, except in the case of very small apartments and hotels.)

Seven Lessons from the bath

So what can we learn from the Japanese bath as it relates to communication and presentation? How is a Japanese bath like a presentation. Here are just seven ways:

(1) You must first prepare.

One must take time to thoroughly wash *before* taking a bath. And one must fully prepare *before* taking the podium.

(2) You must go fully naked.

Shorts and swimming suits are not allowed. You must enter the washing area of an onsen or sentō fully nude (save for a small washcloth). Presenting naked is about removing the unnecessary to expose what is most important. Naked presenters do not try to hide but instead stand front and center and share their ideas in a way that connects with and engages the audience.

(3) Barriers and masks are removed.

Removing our clothes is symbolically removing the facade and the walls that separate us. In today’s presentations, visuals are sometimes used as a crutch rather than an amplifier of our message, thus becoming a distraction and a barrier themselves. Visuals in a naked presentation never obfuscate but instead illuminate and clarify. The naked presenter designs visuals that are simple with clear design priorities that contain elements which guide the viewer’s eye.

(4) You are now fully exposed.

The best type of bathing is in the roten-buro, or the outside onsen, especially in Fall or Winter. The water is hot and the air may be cold, yet you feel alive. Presenting naked is about being free from worry and self-doubt. Gimmicks and tricks and deception are inconsistent with the naked style. You are now transparent, a bit vulnerable, but confident and in the moment.

(5) You are on the same level as others.

Hierarchy and status are not apparent or important naked. The best presentations are less like a lecture and at least feel more like an engaging conversation in a language that is clear, honest, and open. Don’t try to impress. Instead try to, share, help, inspire, teach, inform, guide, persuade, motivate, or make your audience a little bit better. No matter your rank, a presentation is a chance to make a contribution with fellow humans.

(6) You must be careful of the time. Moderation is key.

Nothing is better than soaking in the hot water, but do not over do it. Too much of a good thing can turn unhealthy. A good presenter also is mindful of time and aware that it is not his time but *their* time. Remember the concept of hara hachi bu. Give the audience greater quality than expected, but be respectful of their time. Never go over your allotted time. Leave the audience satisfied but not satiated (i.e., overwhelmed).

(7) Feels great after you’re done.

The bath will recharge you as it warms your body and it will energize your soul. After an important talk, if it goes well, you also feel invigorated and inspired. If we connect with an audience in a meaningful and passionate way that leaves them with something of value — knowledge, insight, inspiration, even a bit of ourselves — then we feel a sense of joy that comes from making an honest contribution. (Photo: with Barry Eisler and other friends at TEDxTokyo after the bath at the Odaiba Onsen, their website is wild.)

Going naked and going natural are the key takeaways from the Japanese bath that, with a little creativity, we can apply to many aspects of our work and daily lives. In this time of ubiquitous digital presentation and other media tools, the tenets of nakedness and naturalness are more important than ever. At the end of the day, it still remains people connecting and forming relationships with other people. And that’s best done naked.

Related

• Photo essay of Japanese sentō by my buddy Markuz Wernli Saito

from presentation zen